Love Tapes at the World Trade Center

Eric Hoyt

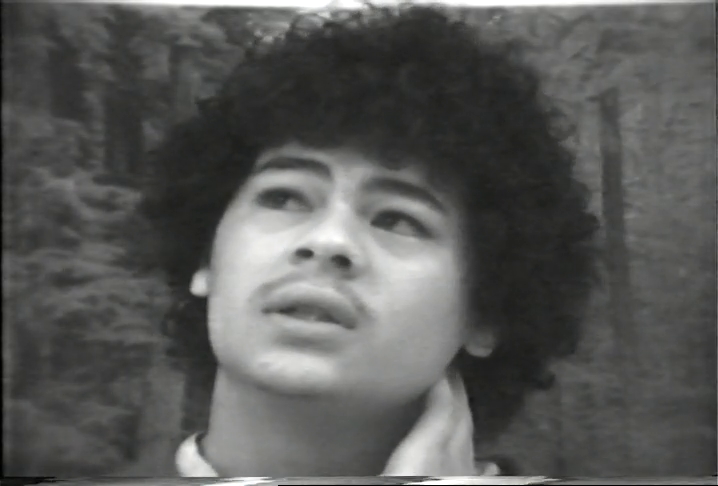

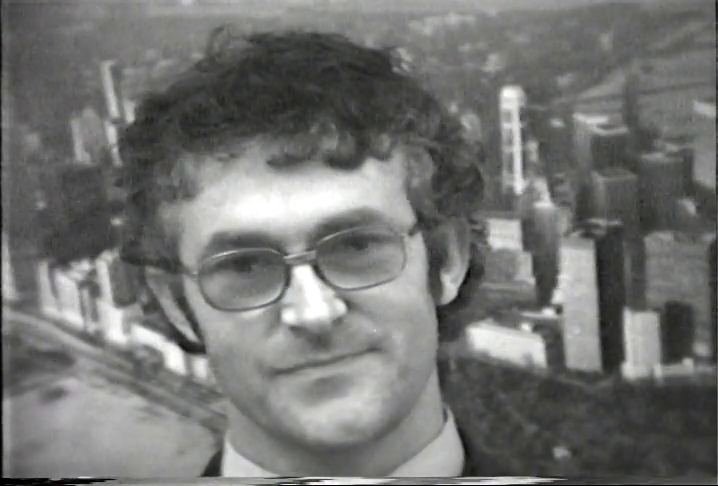

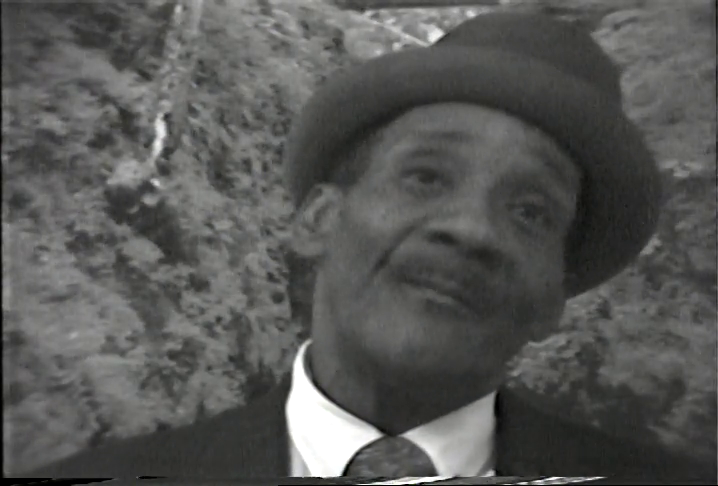

Before the invention of YouTube, Zoom, and Instagram, before a city was transformed by waves of “urban renewal,” the AIDS crisis, and a terrorist attack, hundreds of people took turns entering a video booth inside the World Trade Center and—for exactly three minutes—described what love meant to them.

It was 1980, and the participants came from a diverse range of backgrounds. African Americans, Asian Americans, Puerto Ricans, and people of many other races and ethnicities all recorded love tapes. So too did members of New York City’s gay, lesbian, and transgender communities. Their responses were generally unrehearsed and unpolished, blending joy and sadness, sharing both anecdotes and raw emotions. The participants occasionally invoked clichés, but more often stumbled for the words that could somehow capture feelings, memories, presence, loss.

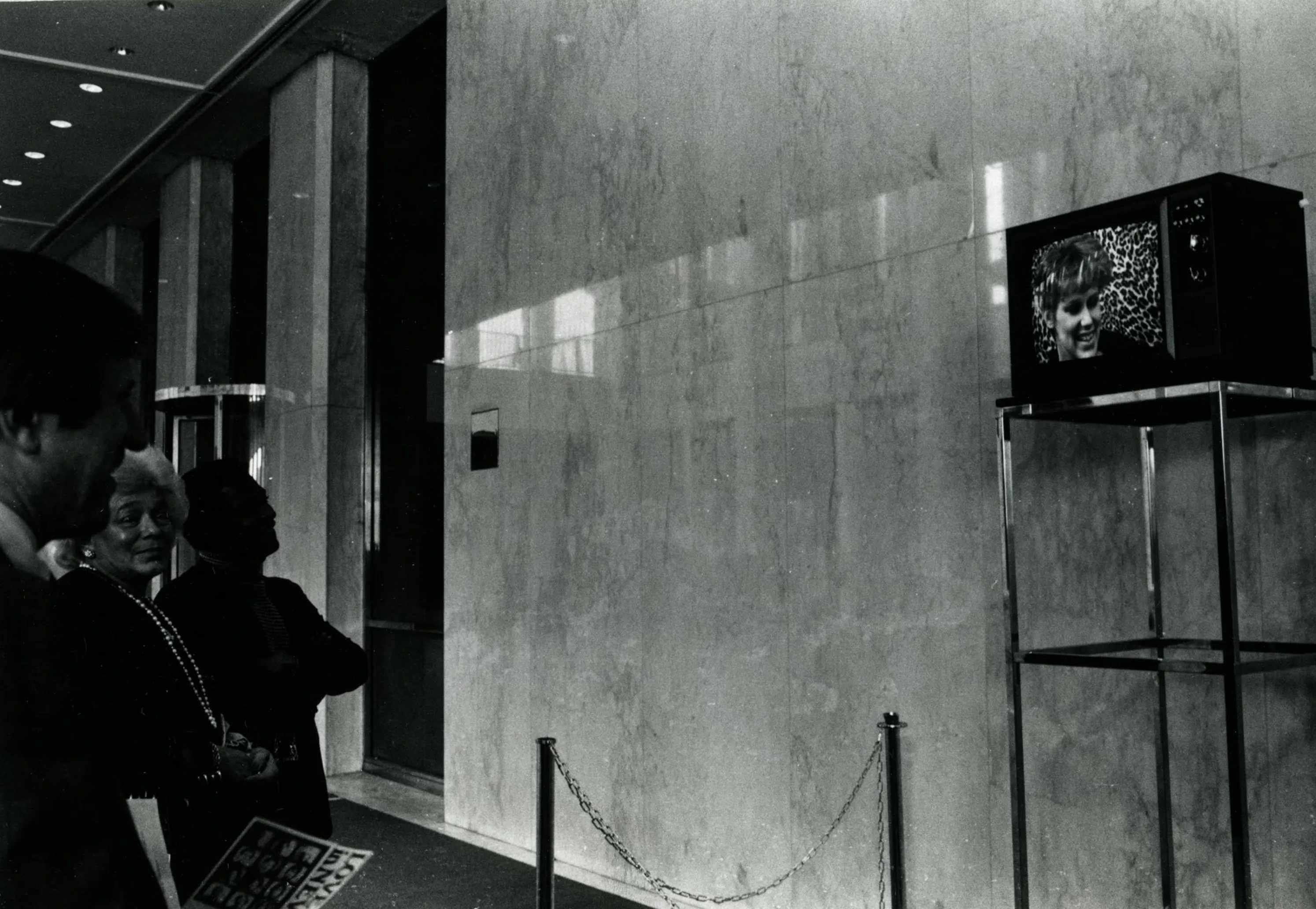

Played on loop on televisions located in the lobby, the completed Love Tapes helped intrigue and draw in new participants.

The Tower Two lobby served as the hub for Love Tapes in New York (1980)—one of numerous installments of Love Tapes that Wendy Clarke facilitated during her career. The Love Tapes format, as conceived by Clarke, followed an intentional sequence:

First, potential participants would have a chance to watch tapes that other people had recorded. Played on loop on televisions located in the lobby, the completed Love Tapes helped intrigue and draw in new participants. The tapes did something else, too. They modeled the qualities of openness, vulnerability, and connection central to the project.

Played on loop on televisions located in the lobby, the completed Love Tapes helped intrigue and draw in new participants.

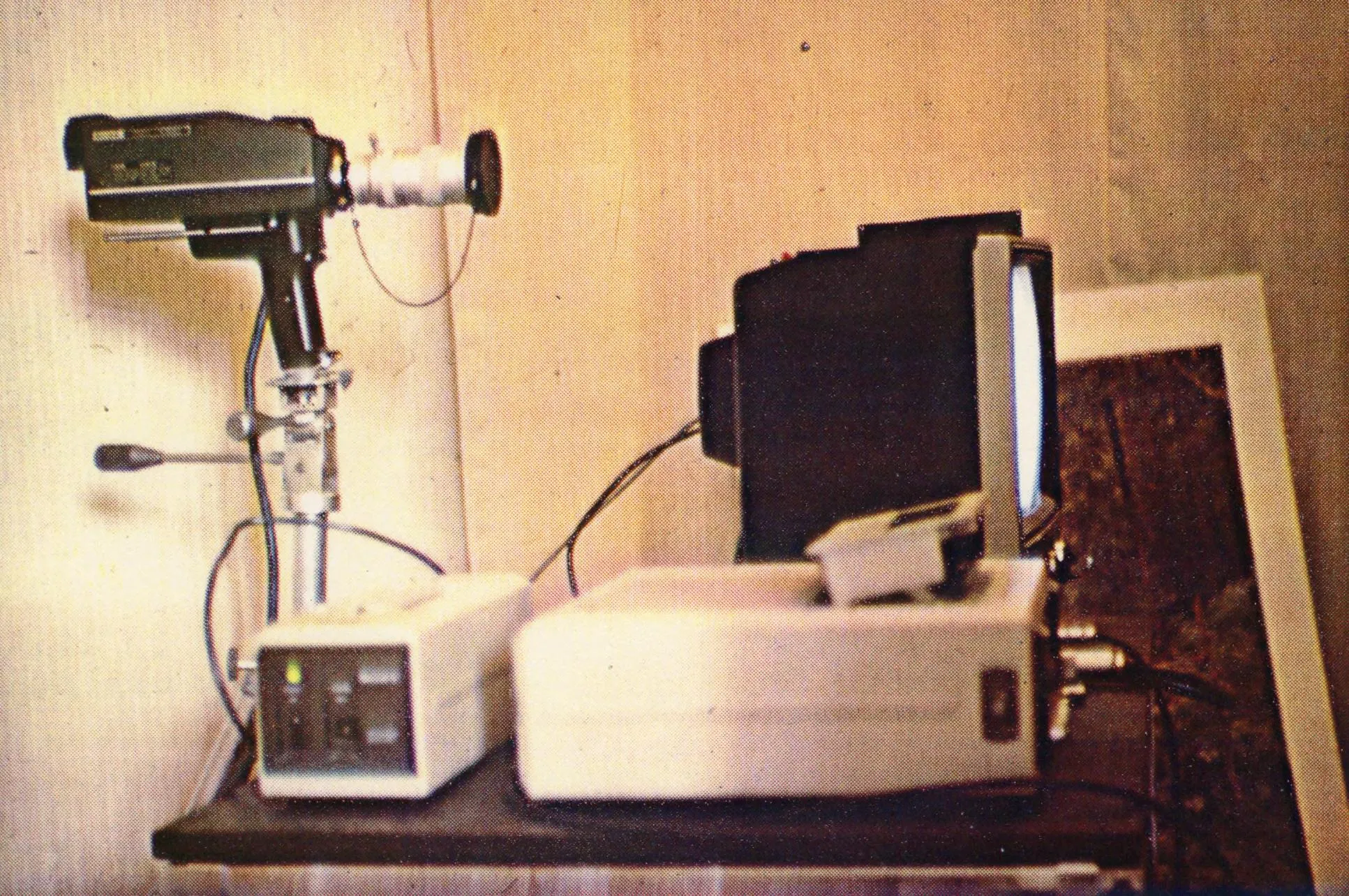

Second, they could choose to record a three minute tape themself—sitting alone in a small booth that had a camera, mic, and monitor (features that decades later would become miniaturized and pre-packaged into phones and laptops). Participants selected from a list of songs to play during the three minutes, as well as choosing a background visual, all of which sparked creativity, energy, and emotion.

Third, after finishing their three minute love tape, participants watched their recording. At this point, they were given a choice between whether to add their tape to the larger collection for public exhibition, or to have it erased. This playback stage of the process was a vital part of Clarke’s facilitation process. It was also deeply ethical, offering participants informed consent and a second opt-in / opt-out moment.

Participants were given a choice between whether to add their tape to the larger collection for public exhibition, or to have it erased.

Fourth, the new love tapes—with participant consent—were added to the collection. In addition to screening them on televisions inside the World Trade Center, they were screened every night on Manhattan cable television, and, over time, many other forums, including this very website you are reading.

In addition to screening the Love Tapes on televisions inside the World Trade Center, they were screened every night on Manhattan cable television

The photos and documents from her collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research—some of which are included above—shed light on Clarke’s techniques for facilitating this participatory format. In an information sheet that she created for volunteers helping with the Love Tapes project at the World Trade Center, she emphasized the potential that existed in the interactions between video and community. She explained that volunteers should:

“[t]hink of this event like a theatre piece, with you as actors, […] as a very big party, a giant social event, where you are meeting and talking with the people around you. Think of yourselves as teachers – Everybody can make art! Think of yourselves as social changers—helping people see and become part of an ACTIVE USE OF TV THAT CAN CONNECT US ALL AROUND THE PLANET.”

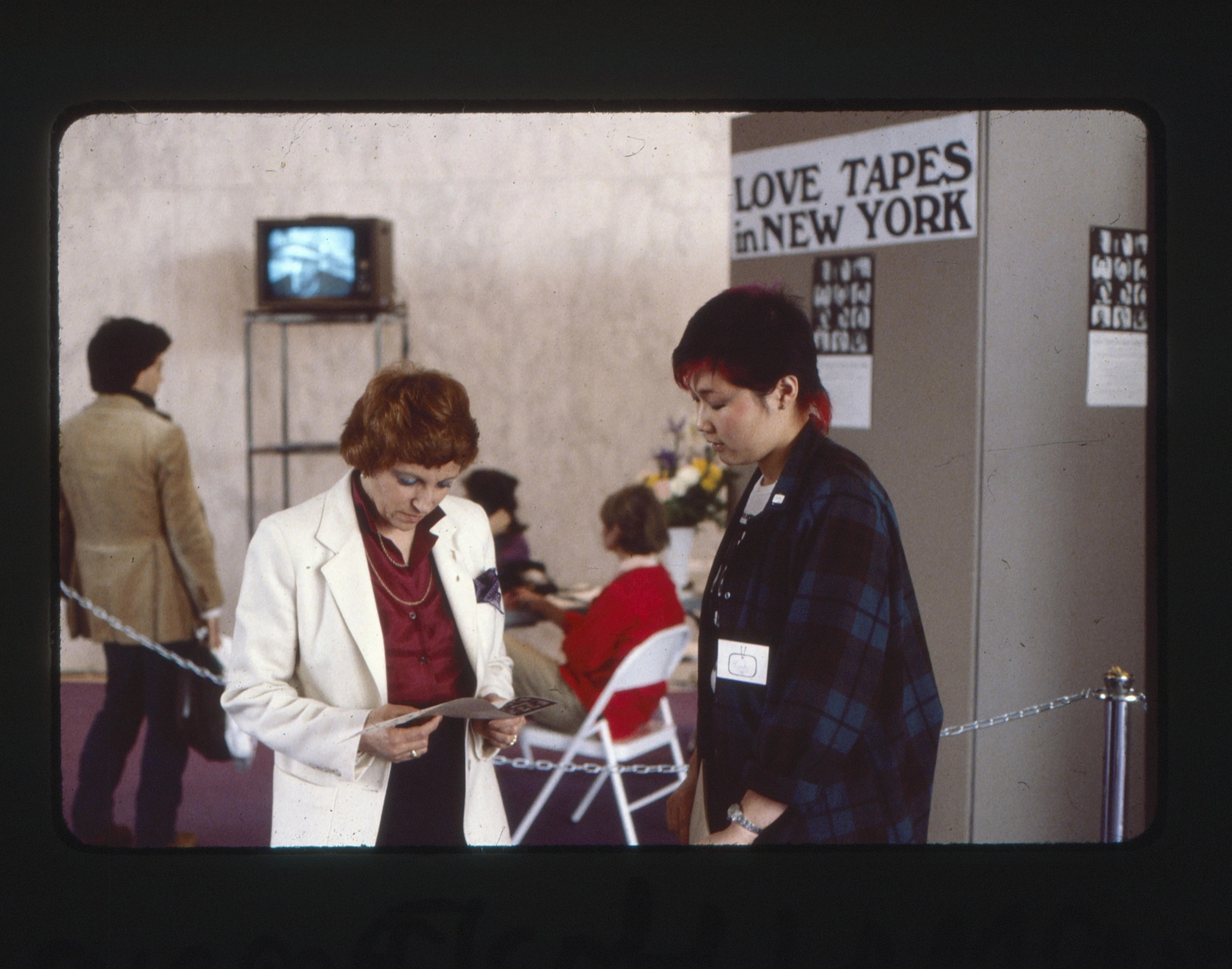

The above excerpt—which ends with a reminder from Clarke to “be yourselves and enjoy!”—showcases Clarke’s sensibilities about building the collection: she wanted volunteers to actively engage in the project, to demonstrate how accessible both art and television are for participants, and to highlight the potential utility of video for social connection and change. The document also highlights Clarke’s role as a team leader in making the project happen.

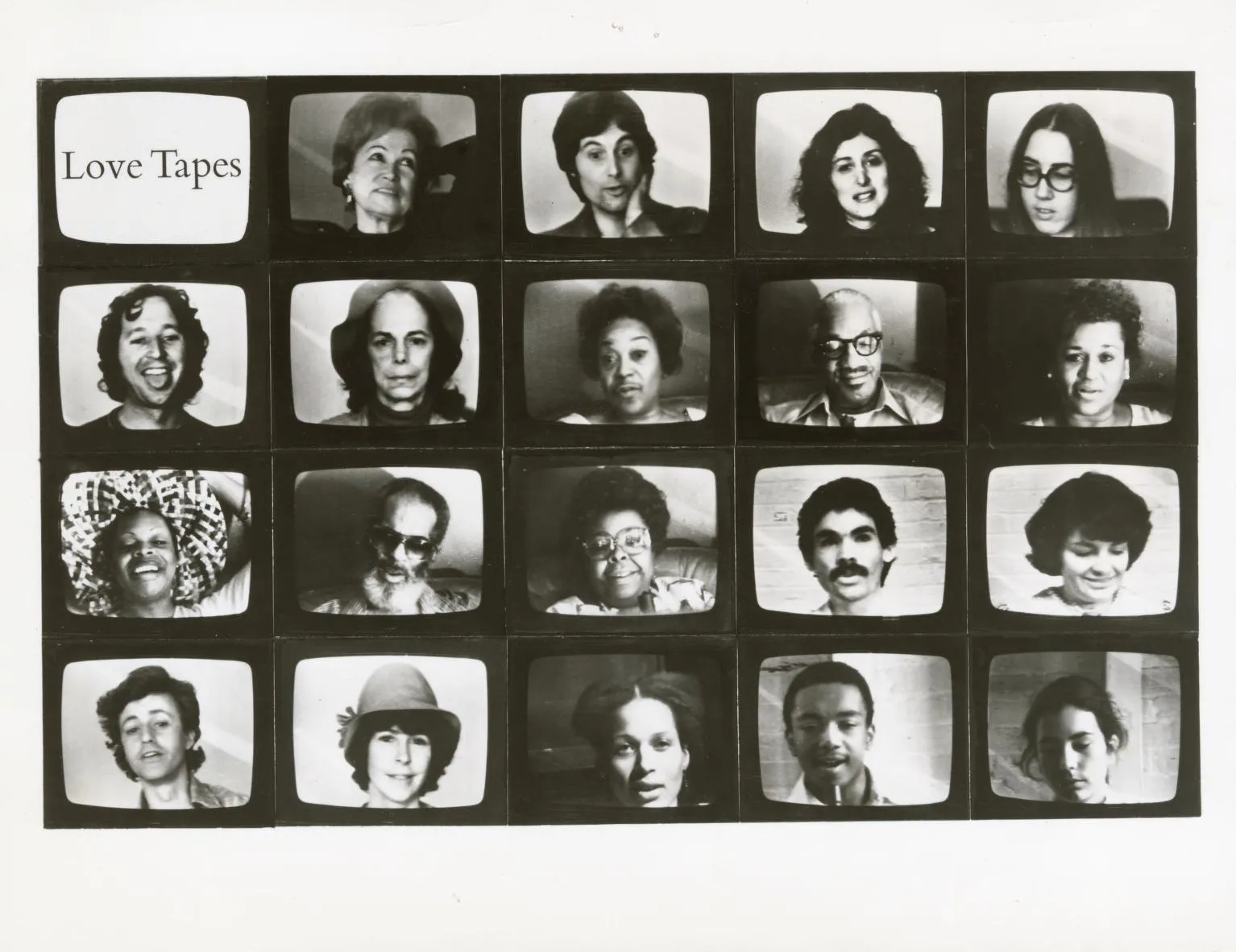

A brochure that Wendy Clarke developed to promote the project further revealed the fluidity between makers and viewers of the tapes. “People begin to see that they no longer need be confined to a passive relationship with TV, but can become part of its content.” The visual design that promoted “Love Tapes in New York”—a Brady Bunch-style assortment of faces in television squares—drove home this idea of community participation within television production.

During her long career, Wendy Clarke facilitated the production of Love Tapes at many other locations. Yet the World Trade Center Love Tapes are uniquely powerful and resonant when we watch them today. We cannot help but remember what happened on the same ground two decades later: Terrorists unleashing hatred and violence on an unimaginable scale, destroying the towers and killing thousands in the process. By recovering joy and creativity that took place at the same site, we connect with the those lives lost, the loves shared in the tapes, and our own thoughts and feelings. It is layers of love, life, and loss. An endless circuit of shared humanity.

Below are excerpts from three of the people who shared their voices and stories in the Tower Two lobby. You may watch all of the World Trade Center Love Tapes here.

Eric Hoyt is the Director of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and Kahl Family Professor of Media Production and a Professor of Film, Media and Cultural Studies in the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.