Seeing Ourselves Survive: Wendy Clarke and Anti-Nuclear Video Activism

Charlotte Procter

Lucy Logan from Tempe, Arizona, travelled to New York City to attend the mass anti-nuclear protest on 12 June 1982 – at that time the largest political demonstration in American history. “I have come to march in protest against the nuclear arms race because it’s the most significant thing facing the world today.” Over a million people gathered in Central Park, rallying against the nuclear arms race as the United Nations Second Special Session on Disarmament convened nearby. Logan’s testimony (recorded at Port Authority Bus Terminal as part of Wendy Clarke’s installation there) was among thousands captured as part of the Disarmament Video Survey - a decentralised media project that invited people from around the world to record short video statements, allowing them to participate in the disarmament debate even if they could not be physically present at the protests. A similar project, that focused on the protests and also included a mass collaboration (over 325 people and groups volunteered) produced and directed by Robert Richter and Stanley Warnow was a film produced by the June 12 Film Group, documenting the protest, viewable here.

However, the Disarmament Video Survey project - produced by Wendy Clarke alongside Skip Blumberg, DeeDee Halleck, Karen Ranucci and Sandy Tolan - built on the organisers’ backgrounds in collective video activism, including work with groups such as VideoFreex (Blumberg), Paper Tiger Television (Halleck), and earlier collaborations between Clarke, Blumberg, and Halleck as members of Shirley Clarke’s TeePee Video Space Troupe. It emerged from a desire to extend the energy of protest beyond its physical limits - offering video as a medium for participation to those who could not attend rallies in person and also utilising the medium of television to reach as many people as possible. It was open to all producers, with shared credit given to contributors and designed to reach the widest possible audience to inspire greater public involvement. The survey began by mailing invitations and production instructions to over 500 art schools, media centres, television stations, studios and independent producers worldwide.

Realised by a vast informal network of over 300 independent videomakers globally, the project used public access TV, closed-circuit screenings and street interviews to bring personal emotion and political urgency into the distant world of international diplomacy. According to the Disarmament Video Survey report held in the archive (dated 11th December 1982), within a month the committee had received sixty half-hour survey tapes from New York, Chicago, Kentucky, Washington D.C., London, India, Holland, Germany, and numerous other locations.

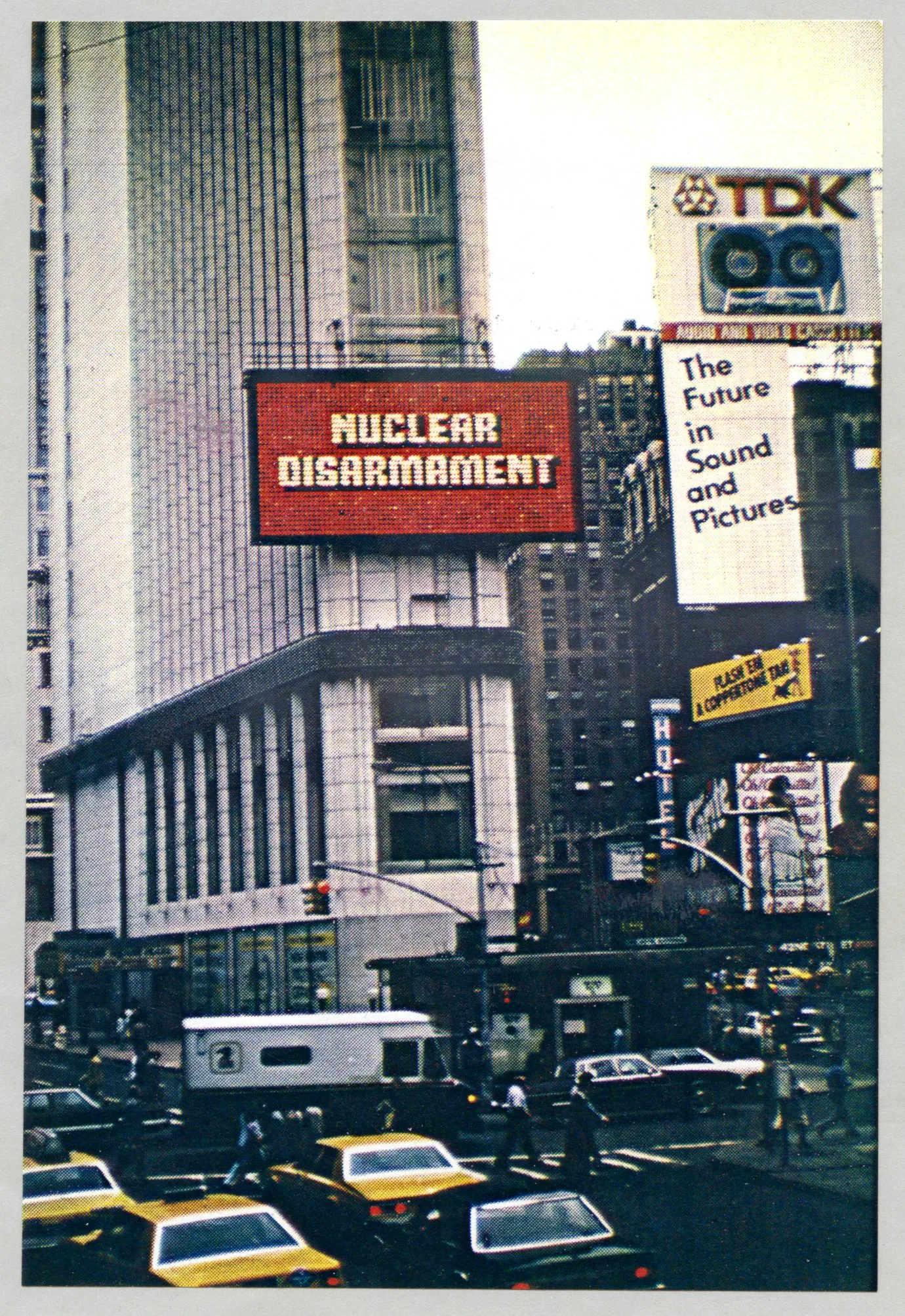

Spectacolour sign in Times Square

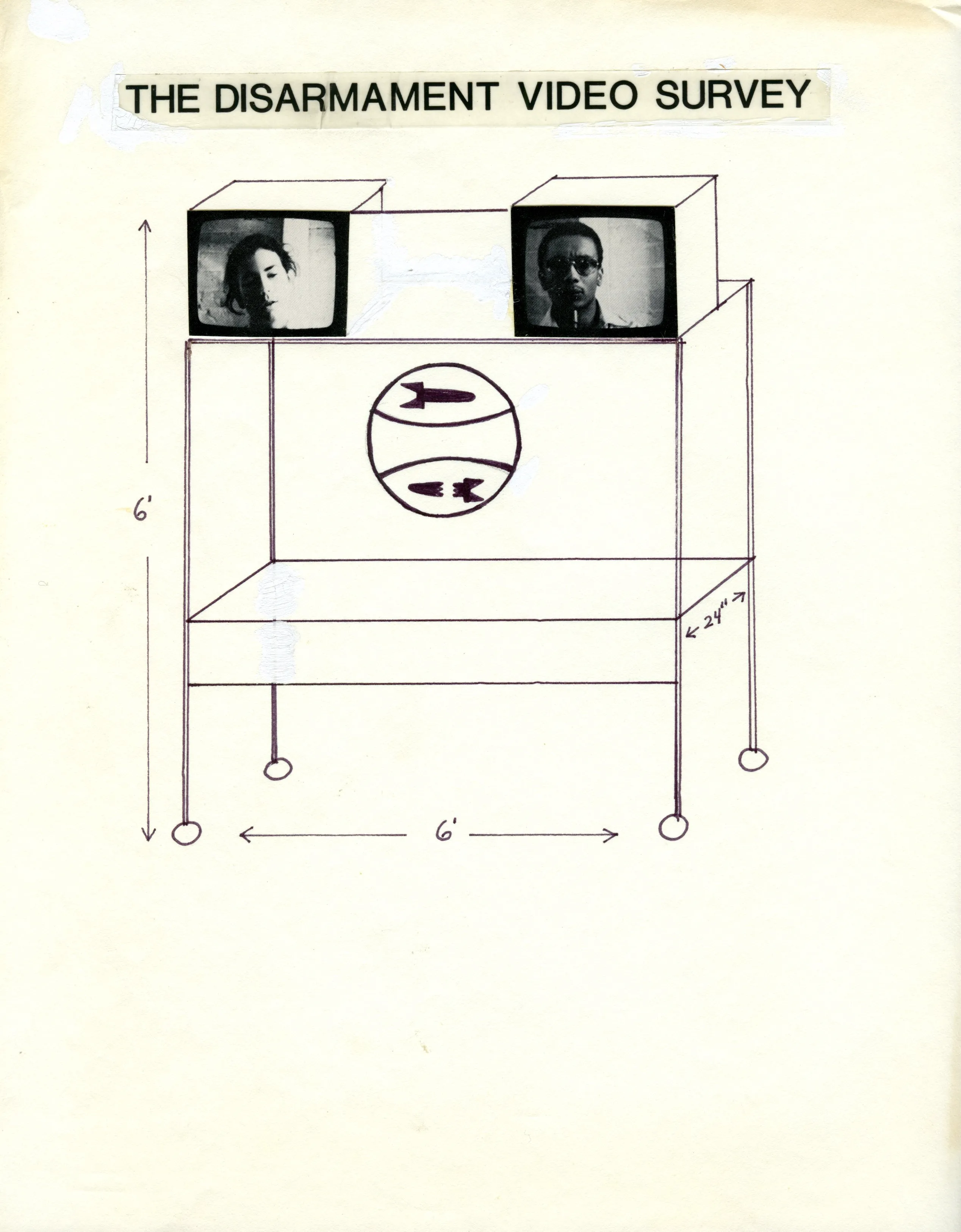

Wendy's diagram for the playback monitor installation at Port Authority

In addition to being one of the principle organisers of the survey, Clarke’s major contributions to the project were two prominent public installations in New York. On Monday 7 June, the Disarmament Video Survey was installed in Times Square for five days. A key component of the installation was a 23-foot Winnebago van, donated by the owner of Nathan’s Deli, which Clarke coordinated to house monitors and playback systems for showcasing interviews from around the world. As Clarke recalled, “The owner of Nathan’s Deli also knew the people who had the sign that was used to drop the ball on New Year’s Eve. So I programmed the sign.” The computer-animated Spectacolour sign in Times Square promoted the project throughout the day, inviting commuters, shoppers and tourists to record their opinions. Another installation was set up each afternoon at the Port Authority Bus Terminal, which attracted commuters from all over the country. The participants could view themselves on a monitor as they recorded their contribution.

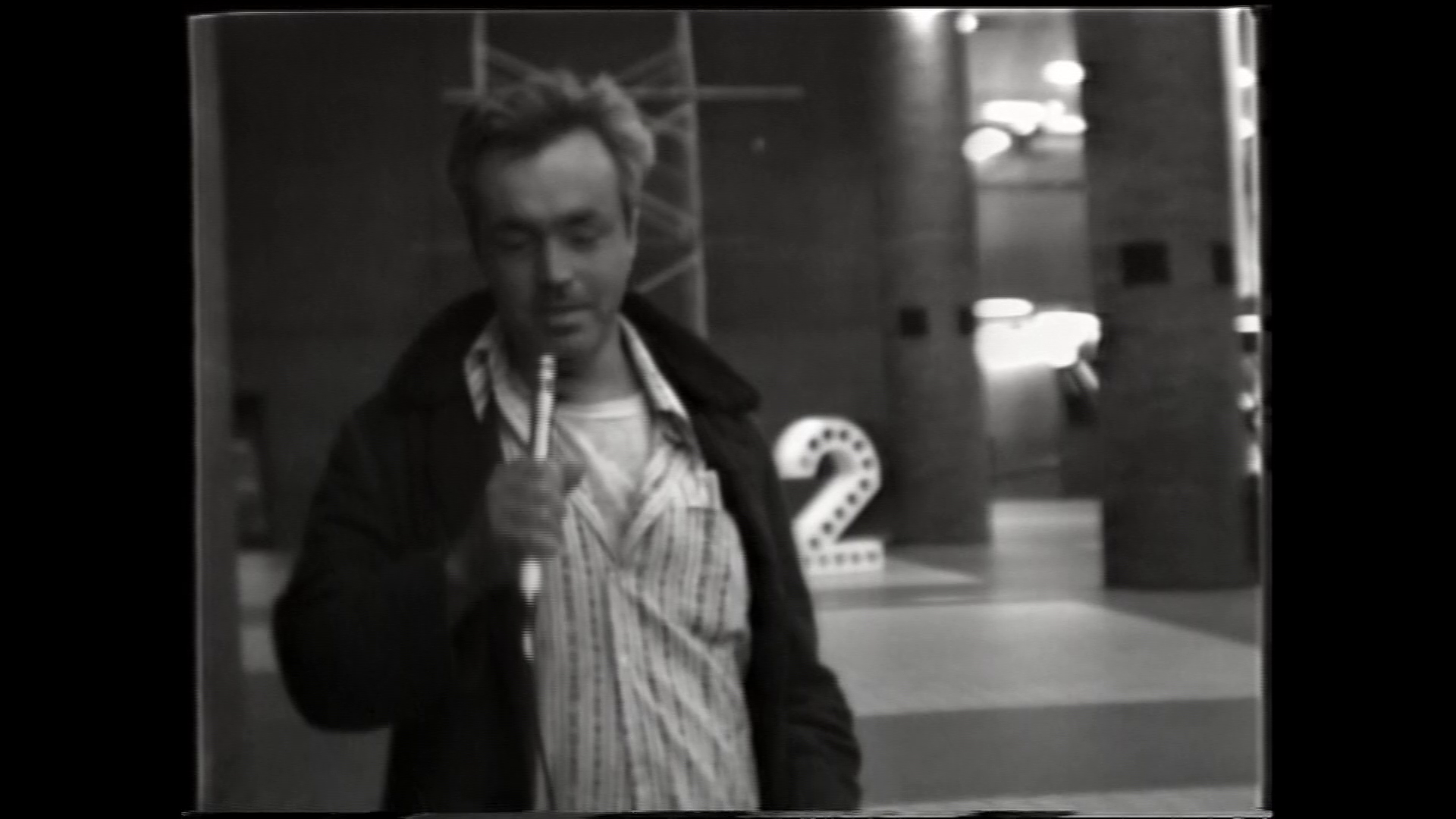

Repurposed 23-foot Winnebago van donated by the manager of Nathan's Deli

Clarke reflected in 1982: “The most exciting part of the van project was that people on the street were reacting to the people on the screen. (Groups of people with both similar and dissimilar opinions started discussions based on the tapes that were rational as opposed to emotional bantering.) It was really inspiring to see.” Showing live interviews as they were being recorded increased public participation on the street. Within four days, more than 1,200 people had shared their views via the survey van and many of these were broadcast on Manhattan Cable.

Clarke’s work on the project built on ideas she had explored in her earlier project Love Tapes (1977–ongoing), the long-running series where people speak directly to the camera about love, creating personal and often intimate video portraits. Reflecting on the format, “The public stated their opinions when they were alone, direct to camera… much like The Love Tapes,” Clarke explained. In both projects, the camera becomes a mirror: personal testimony captured as a collective record.

Gabrielle, a waitress in Manhattan, is keen to link the struggle for disarmament to past and ongoing military interventions led by the United States.

Click here to view full tape.

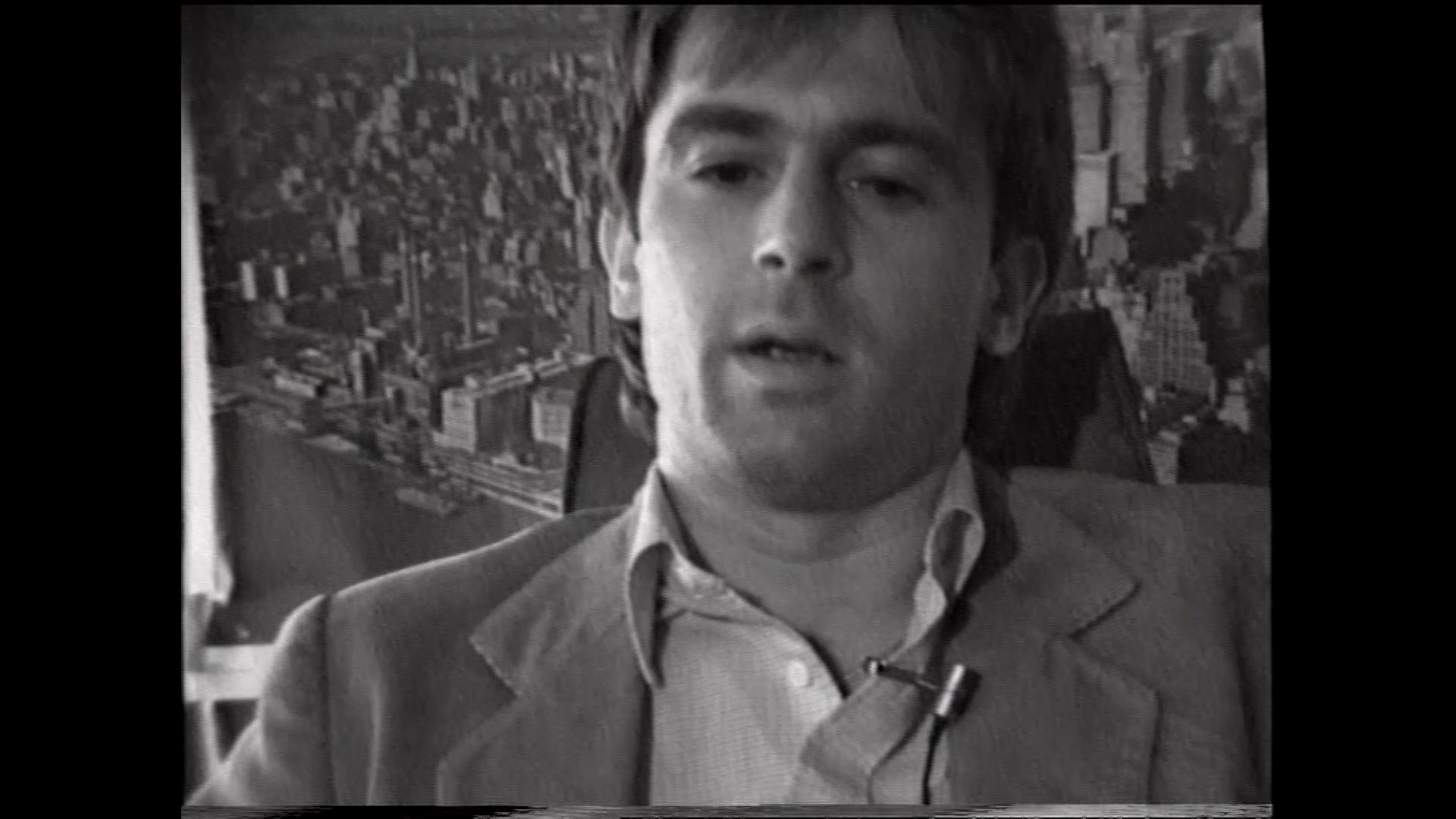

The tapes filmed in the Times Square bus show participants seated in front of a wall covered with a New York cityscape. This indoor, more intimate setting appears to encourage more reflective responses, similar to the Love Tapes. In contrast, the tapes filmed at Port Authority feature participants standing in a busy station, with escalators busy with people seen in the background. Here, contributors need guidance on how to position themselves within the frame and how to hold the microphone. These responses sometimes feel shorter, some feel more urgent. Gabrielle, a waitress in Manhattan, is one such participant. She is keen to link the struggle for disarmament to past and ongoing military interventions led by the United States. In her contribution, she also reflects that while her boss at the restaurant supports nuclear disarmament, he does not share her views on the Equal Rights Amendment and “he doesn’t think that there should be money for jobs and he doesn’t even want to pay us minimum wage at the restaurant.” Many participants connect between disarmament and how it intersects with broader social and economic issues. These reflections position nuclear disarmament not as an isolated concern, but as one linked to wider struggles, such as those for workers’ rights.

Participants like Samuel Patterson share deeply felt responses to the nuclear threat.

Click here to view full tape.

Throughout the Nuclear Disarmament Survey videos, participants share deeply felt responses to the nuclear threat. Samuel Patterson, identifying himself as “a senior citizen… originally from the West Indies, but I’ve been in New York 64 years,” said: “I was in World War One… I’ve seen sick and wounded people… I don’t want to see no more of that. Forty billion dollars spent down in Washington to make bullets, to kill people, when we want homes… I don’t even have a home to live in, just for a few more years to live.”

Lauren Johnson, another participant, reflected: “It seems to me that humanity has the incredible knowledge to build nuclear weapons that are threatening us all, but didn’t have the wisdom not to? Just because the powers that be could have done, doesn’t mean they should have… In a world that is still wracked with racism, sexism, ageism, classism, homophobia and everything else, it’s clear that we didn’t have the capabilities to handle what our intelligence told us we could do.”

"In a world that is still wracked with racism, sexism, ageism, classism, homophobia and everything else, it’s clear that we didn’t have the capabilities to handle what our intelligence told us we could do."

Click here to view full tape.

Michelle Joyner, 20, a student at Hunter College, explained: “I am really behind the disarmament programme in the United States and in European countries and in the Soviet Union, because I think that it’s a really alarming threat to our society, especially now. And I think it’s a threat to our future generations, not only because of the possibility of nuclear war, but because of the extinction of their education and their culture of art and music, because the budget is going toward the military rather than to their benefit…”

Joy Dreyfus from Hastings-on-Hudson added: “I fear very much that it’s threatened not only by the possibility of nuclear warfare, but also by the possibility of the people feeling that they don’t really have any role in what happens in the future… People are being forced to become more alienated because they’re not really given any of the sort of encouragement or the support that they need.”

A few of the contributors made connections with broader environmental issues, including nuclear energy and uranium mining, and how these relate to the nuclear arms movement. Although most of Clarke’s tapes from the Nuclear Disarmament Survey comprise Americans—specifically New Yorkers or others passing through Port Authority—the protest also attracted participants from Canada. Scott Morrison, from Calgary, Alberta, had travelled to attend the rally and, in his statement, connected the movement to his local context: “There’s uranium that’s being mined in Saskatchewan, Canada. And we’re against that too, because we feel that that’s part of the nuclear arms movement…We’d like to see a weapons-free zone in Canada and no building or testing or any sort of mining, uranium mining or anything to do at all with the uranium and nuclear weapons testing…”

"When this informal network will come together again will be determined by world events. But this project again proved the existence of a politically committed video community."

- Disarmament Video Survey Project Committee

Not all participants supported disarmament; a few expressed strong concerns that it would leave the United States vulnerable to perceived threats from Russia. Others endorsed the concept of disarmament in principle but believed that, given the existence of nuclear weapons, a complete reversal was no longer feasible.

The project committee later wrote: “When this informal network will come together again will be determined by world events. But this project again proved the existence of a politically committed video community.” The Disarmament Video Survey emerged at a time when video art and political activism were converging across borders. In Britain, artist-activists involved with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp were similarly using video to amplify their anti-nuclear message.

The Disarmament Video Survey underscores video’s potential as a tool for social change, demonstrating its capacity to function as an active platform for expression and debate. In line with Clarke’s other projects, the resulting tapes were screened across a wide range of spaces - not only through public installations, but also screenings in art galleries, classrooms, and community centres. As with the Love Tapes when exhibited at the World Trade Center, this was accompanied by broadcasts on Manhattan cable television. Such broad dissemination highlights the reflexive nature of video and its accessibility, which was especially significant to the project’s core aim: empowering ordinary people to feel they had a voice on this critical issue.

If The Love Tapes asked, “What does love mean to you?”, the Disarmament Video Survey asked, just as urgently: “What does survival mean to you - and to us all?”

Charlotte Procter is an archivist, curator, and collection & archive director at LUX. Since 2013, she has been a member of the Cinenova Working Group, a volunteer collective dedicated to the ongoing preservation and distribution of the Cinenova collection, as well as working on special projects that seek to question the conditions of the organisation.