LGBTQ Representation in Wendy Clarke’s Video Projects

Matt St. John

In a tape from Wendy Clarke’s Remembrance, an elementary school teacher named Bruce discusses the lasting impact of his partner Michael, a nurse who died from AIDS, while trying to calm his squirming dog Rex. After whispering “stay” and “sit,” Bruce tells the story of his relationship with Michael with a focused confidence, even as Rex waves his paws and strains to look at things offscreen. Recorded in 1996 at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Bruce’s tape with Rex demonstrates the combination of emotional reflection and unpredictable, spontaneous elements that characterizes much of Clarke’s participatory video art.

As this tape suggests, Clarke’s work from the 1970s through the 1990s consistently included LGBTQ individuals. In this way, her projects provide a historical record of a time of increased openness alongside immense tragedy and loss, as HIV/AIDS had an enormous impact on the queer community. Videos by LGBTQ participants, which appear throughout Clark’s projects, contain a vast emotional range, from joyful to mournful, angry to grateful, and sometimes all of these feelings at once. While there are examples across her career, three projects involve LGBTQ people most frequently or prominently: Love Tapes, Growing Up Gay: The Out Tapes, and Remembrance.

During a Love Tape, a man tells the story of falling in love with his friend.

Click here to view full tape.

Between its sheer volume and its recording in major cities like New York and Los Angeles, the Love Tapes project includes many LGBTQ contributors. Clarke made the majority of Love Tapes from the late 1970s into the early 1990s, and gay participants often discussed their love lives without focusing on topics like homophobia and discrimination, which dominated media discourse about LGBTQ people at the time. In a tape recorded at UCLA in 1982, a young man talks about feeling a strange disdain for another guy that he eventually realized was love. Later, the same man recounts the experience of falling in love with one of his friends, recalling the accompanying sensation as a whole “magic” and “violins” feeling. In a 1979 tape from Hartford, Connecticut, another man describes meeting a guy in Boston who became his first real love, reflecting on how this differed from past experiences with unrequited love. In both of these examples, gay men describe their relationships in terms of crushes, confessions, and confusing feelings, just like other participants in the Love Tapes project, regardless of their sexual orientation. In the context of media from this time, such tapes are rare records of gay men’s feelings and experiences expressed in solely romantic, emotional terms, without being tempered by a complex, often negative, social context.

Two sisters discuss their different paths and identities in a Love Tape.

Click here to view full tape.

LGBTQ identities also come up in the Love Tapes when participants discuss other relationships and types of love, beyond just romance. In a 1993 tape, two adult sisters talk about their love for one another in the face of an upcoming surgery for one of them, while noting the major differences in their lives: one is the straight housewife of a farmer, one is a lesbian artist/drug counselor, but they share many similarities because of growing up together in a difficult situation. The lesbian sister says, “Love, to me, is when you don’t have that boundary of looking good or making a good impression because she knows from whence I sprung,” while pointing to her sister, nodding, and tearing up. Like the gay men in the previous examples, the Love Tapes project offers this woman the opportunity to discuss love in her life in a nuanced way, with her lesbian identity being just part of her story, but not the whole story. Such examples from Love Tapes provide nuanced representations of LGBTQ people in their own words, distinct from mainstream media representations of the period.

Wendy Clarke also collaborated with psychologist Ralph Bruneau on a 1995 project seeking to highlight LGBTQ stories specifically: Growing Up Gay: Out Tapes. Motivated by his frustration with psychological models that treated homosexuality as a pathology, Bruneau hoped to educate people about the diverse experiences of the gay community, rather than leave in place assumptions about growing up as a gay person that are based on homophobic psychological literature. In this video project, each participant would hold up a photo from their past, usually from childhood, and talk about what they see in that person and how they have changed. The people in the Out Tapes describe a range of experiences, but there’s an emphasis throughout on family relationships and the discomfort created by other people’s heteronormative expectations. For example, a man named Dalton describes the difficulty of childhood bullying because he was creative, loving, kind, sensitive, and fun, but ultimately feels that the experience made him strong. Another man, Tom, talks about feeling out of step with his family but knowing he wasn’t bad, even as a child, and now feeling eternally grateful that he is different. In such examples, the O_ut Tapes_ participants reflect on challenging childhood experiences of discrimination and homophobia, with also frequently affirming the pride and gratitude that they now feel about their identity.

A man describes his experiences in the Filipino and gay communities in Growing Up Gay: The Out Tapes.

Click here to view full tape.

Many of the participants are gay white men, but queer people of color and women also contributed to the Out Tapes, often explaining how their experiences are distinct. One man describes feeling alienated by many gay institutions because they’re so white, while also expressing frustration with frequent homophobia in his Filipino community. Despite the challenges he identifies, he ultimately focuses on the power he draws from a society that treats him as invisible, as he feels immense freedom. A woman named Pam discusses her childhood memories of not conforming to expectations for little girls. She worked hard to hide her love for baseball, with a secret baseball card collection and a habit of playing catch with her dad at a park far from their home. Pam ends her video by stressing the importance of speaking out as a lesbian: “One reason I wanted to participate in this project is I think it’s important for women to have a voice and to speak out. And it seems in our society, even in the gay society, men seem to have a louder and a greater voice.” The Out Tapes series reflects the tendency to hear more from men (and particularly white men), even within the LGBTQ community, but the perspectives of women and people of color in Clarke’s video art stress that the LGBTQ experience is far from monolithic.

With Remembrance, Wendy Clarke turned her attention to the AIDS epidemic, and this project frequently involved LGBTQ people because of the epidemic’s massive impact on the community. The project grew from Clarke’s experience as an art therapist working with HIV positive incarcerated men in California. Clarke and the men made a talking stick, inspired by African storytelling oral traditions and Native American ceremonial councils, to help the person holding it speak the truth. The talking stick included leaves displaying names of incarcerated men who died and a poem written by one of the men, and participants used the stick to control the camera.

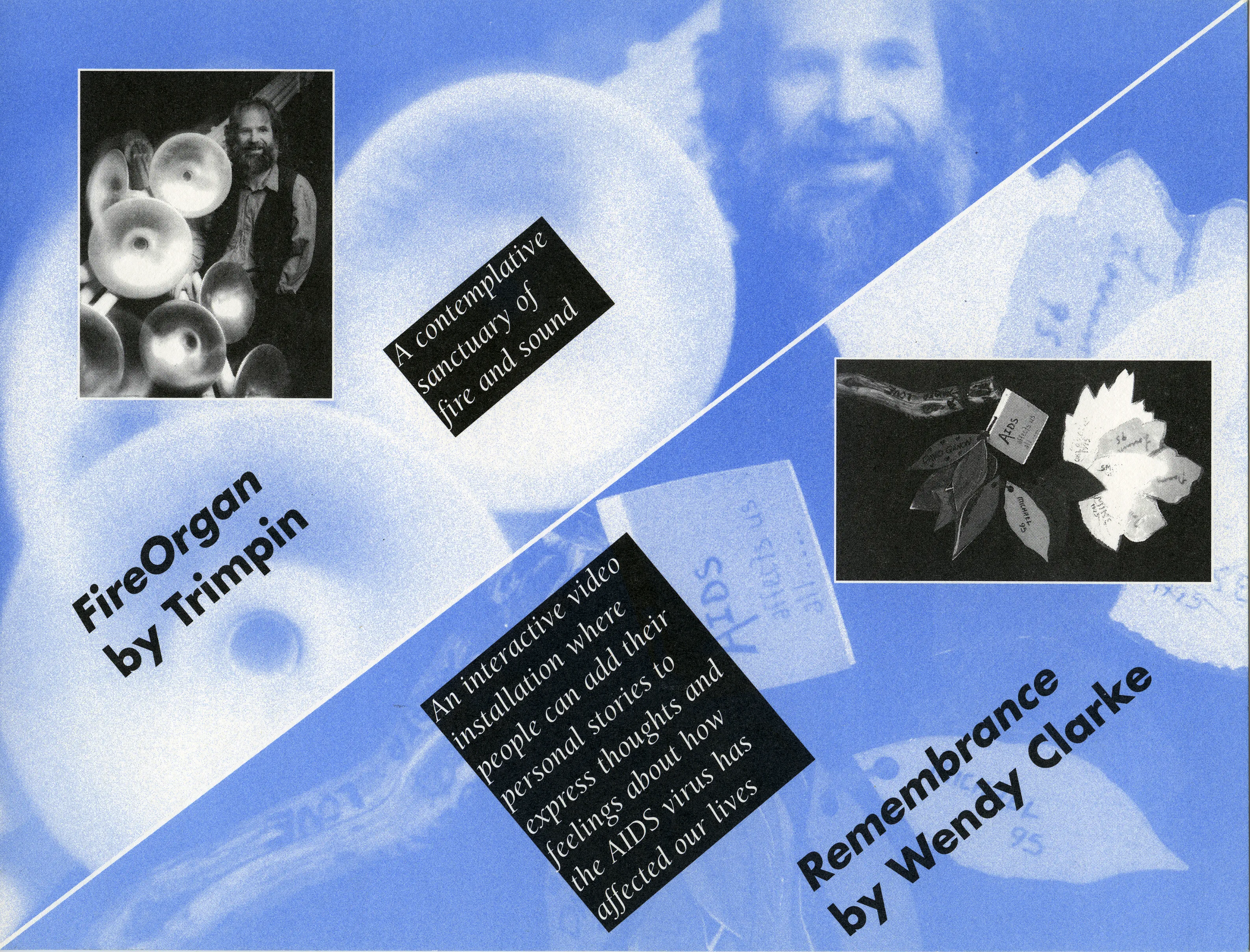

A postcard advertising the “What About AIDS?” exhibition at the Exploratorium.

Remembrance was introduced as part of the “What About AIDS?: Science, Art & Human Stories” exhibition at the Exploratorium in San Francisco in 1996. Marketing materials described it as “an interactive video installation where people can add their personal stories to express thoughts and feelings about how the AIDS virus has affected our lives.” Later that same year, Clarke brought the project to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. In keeping with Clarke’s other video art, Remembrance features participants representing a range of age, race, gender, and sexuality. In this case, participants also have various connections to AIDS. Some individuals discuss their AIDS diagnosis, others describe losing family members or friends to AIDS, and many share their general fear and sadness about AIDS. In other videos, activists plead with viewers to practice safe sex.

Throughout these videos, participants share stories of queer life and community in the mid-1990s, particularly in their intersections with HIV/AIDS. One man pays tribute to artists who visited the Walker, providing a testament to gay filmmakers like Marlon Riggs, Peter Adair, and Derek Jarman who died from AIDS during this time. In another video, a man named John describes his sadness that AIDS now feels like a normal occurrence when he hears about his friends’ diagnoses. One woman at the Walker Art Center discusses her artist friend Cindy, who has been living with HIV for at least a decade, and she also references other gay men in the community who have been diagnosed with HIV or AIDS. At the end of her video, she describes feeling like the whole world has AIDS, since it has affected so many people in her social circles in Minneapolis.

Jim discusses living with AIDS in Remembrance.

Click here to view full tape.

A man named Jim recorded at least two videos for Remembrance at the Walker. He appears on screen in a black turtleneck with red suspenders. In one of the videos, he points out that his turtleneck displays the words “AIDS Medicine & Miracles,” next to his red HIV/AIDS awareness ribbon. Jim describes his experience beating the odds and living with AIDS for nine years, even after pneumonia, cancers, and a stroke, and his memories of losing dozens of friends and several boyfriends. His tapes underscore the enormous loss in the queer community at this time and the discrimination they continued to face, with a story of extended family who cut him off for years because he was gay. In one of his tapes, Jim reflects on his motivation for recording the video, saying, “I come here in remembrance of those people that I’ve loved that have died, and those I know that will be dying. And I won’t always be here to be able to do that, but now I can by putting something in words to share with other people.”

Clarke’s video art with the LGBTQ community features multiple statements like Jim’s, about the importance of bearing witness in a project that can be viewed by others. This website makes it possible for a new generation of viewers to hear from Jim and all the other LGBTQ participants in Clarke’s projects. The frequent presence of queer representation in Clarke’s videos is an effect of her dedication to public participation, as well as her commitment to providing marginalized groups with a platform, like Growing Up Gay: Out Tapes. From general reflections on relationships and romance in the Love Tapes to stories of living with HIV/AIDS in Remembrance, Clarke’s projects include dozens of portraits of LGBTQ life from the 1970s through the 1990s, offering profound individual stories as well as pieces of a broader social history.

Matt St. John is a Manuscript Specialist at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. His doctoral dissertation, “United Slates: The Evolution of the American Film Festival System”, traces the evolution of the American film festival system, revealing the emergence of globally-recognized, regional, and identity-based festivals from the 1960s to the present.