Facilitation Art: The Ethics of Wendy Clarke’s Video Practice

Michael Renov

The scale and ambition of The Love Tapes (with its unstated goal: what if everyone made a love tape?) that best exemplifies the profoundly ethical character of Clarke’s practice. It does so, first of all, by ceding the primacy of place for the creative act from self to Other. Clarke had discovered video as art at the moment of its radical invention among the cultural elite. She took up the tools, explored video’s plasticity as a medium, its potential for intimacy and self-interrogation, its portability and participatory potential. So did many others.

At the conceptual heart of The Love Tapes and Clarke’s role as facilitator is the bestowal of a single animating word, love, the project’s perpetual but preternaturally fluid theme. It is the mana-word in the Barthesian sense. From Roland Barthes’ Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes: “In an author’s lexicon, will there not always be a word-as-manna, a word whose ardent, complex, ineffable, and somehow sacred signification gives the illusion that by this word one might answer for everything?” So in addition to the strict spatio-temporal parameters and technical supports provided, the bestowal of the manna-word love is an essential feature of Clarke’s facilitating practice.

More than thirty years ago, I wrote an essay entitled “Video Confessions” in which I traced the ways that video, in the hands of some artists – among them, George Kuchar, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Ilene Segalove, Vanalyne Green, Sadie Benning and Wendy Clarke – had emerged as an alternative platform for confession. By the late 20th century, Catholicism’s version of confession, the Sacrament of Penance or Reconciliation, played an increasingly diminishing role as religious affiliation in the U.S. and elsewhere showed dramatic decline (as well as more than a 20% drop in the past two decades according to a recent Gallup Poll). And yet, confessional culture boomed. Indeed Foucault, via the elaboration of his repressive hypothesis described in the first volume of The History of Sexuality (repression produces discourse), claimed that “one goes about telling, with the greatest precision, whatever is most difficult to tell… Western man has become a confessing animal.”

"The confession is a ritual of discourse… a ritual in which the expression alone, independently of its external consequences, produces intrinsic modifications in the person who articulates it: it exonerates, redeems, and purifies him; it unburdens him of his wrongs, liberates him, and promises him salvation."

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I

Crucial to Foucault’s theorization of confessional culture was the notion of power. Foucault insisted that the ritual act unfolded always within a power relation; the interlocutor was necessarily an authority “who requires the confession, prescribes and appreciates it, and intervenes in order to judge, punish, forgive, console, and reconcile.” In my “Video Confessions” essay, I posited a trio of key interlocutors for the confessional act in contemporary life – the three P’s: the priest, the police officer and the psychiatrist – and corresponding confessional sites (confessional booth, police examination room, the couch) whose representations are familiar from popular culture. To these three interlocutors I hoped to add a fourth: the video artist. But where, one could ask, does the power dynamic reside for the video artist?

To understand how video finds its way into the confessional mix, one need only recall a strand of the early theorization of video in the 1970s and early 1980s, namely inquiries into video’s intrinsic properties, its specificity as a medium, its ontology. The cinema had, even before the turn of the 20th century, inspired a great deal of philosophizing as to its status as the seventh art, one whose unique affordances separated it from its precursors. But video took arguments surrounding medium specificity to new heights and for good reason: the materiality of cinema – its matrix of photographic and photochemical properties as well as the indexical status of the images captured – had been supplanted by the electronic: a succession of discretely captured images imprinted on celluloid now replaced by a stream of electronic pulses, a circuit, a self-contained loop. That latter description, the self-contained loop, once one of the most alluring features of video for the confessional video artists of whom I speak, has less purchase in the age of smart phones, digital streams and the worldwide web. But this is another topic far beyond the scope of this paper.

The materiality of cinema had been supplanted by the electronic.

But where or how does power reside in the self-contained loop of the video artist’s confessional practice? After all, the video confession I had in mind was a first-person affair with the artist addressing the camera directly, typically in closeup. This variant of the confessional act would seem to be stripped of a human interlocutor who prescribed, punished or forgave. But, in its place we might identify the implied power (or potency) of the medium itself which promises both a preserved record of the expression and an imagined and incommensurable audience for it. The power of video, leveraged by but also ensnaring the artist, lay in its self-contained, looped intimacy wed to an endless potentiality.

Should we feel the need to bolster this claim, recall that Marshall McLuhan, that early shaman of the televisual, had described TV as an extension of the nervous system, a kind of electronic prosthesis possessing an unlimited power of expansion. The medium itself was the source of the power that these confessional artists mobilized and of the circuitry in which they were enmeshed.

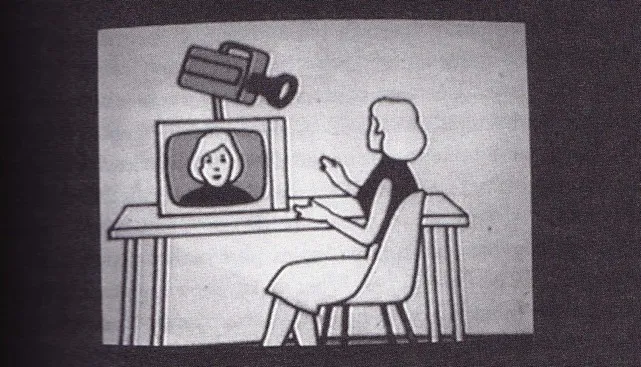

Before turning to the realm of ethics essential to my understanding of the special character and contribution of Wendy Clarke’s oeuvre, I offer a description and brief analysis of her single most significant project. Clarke’s “Love Tapes” project consists of more than 2500 short tapes made by people from many lands over more than forty years. The minimalism of the concept is compelling: individuals of every age and background are given three minutes of tape time in which to speak about what love means to them. In many cases, a small booth-like structure was erected, usually at a public site (a mall, a bus station, a prison), containing a chair, a video camera mounted for a frontal, medium close-up, and a monitor. Each participant chose a backdrop and musical accompaniment as mood dictated before activating the camera. Clarke was nearby facilitating, supplying her subjects with the opportunity and tools to produce the work. The subject-participant was necessarily the first audience of the piece, and, upon review, could opt in, allowing the tape to be screened, often at an on-site installation that might incite others to produce their own tapes. The tapes of those who opted in then entered the collection.

Shirley Clarke’s TeePee Video Space Troupe included as participants, at various moments, members of the VideoFreex commune as well as an array of cultural superstars.

But what of ethics in this play of power and potentiality? In a recent interview with Kristin MacDonough appearing in the Video Data Bank catalogue, Wendy Clarke has described her first encounters with video in the early 1970s when her mother, Shirley Clarke, famed downtown artist and a recent recipient of multiple Sony Portapacks from the New York State Council on the Arts, formed the TeePee Video Space Troupe. Taking on the model of the jazz ensemble, the Space Troupe participants included, at various moments, members of the VideoFreex commune as well as an array of cultural superstars: Nam June Paik, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Arthur C. Clarke, Nicholas Ray, Agnes Varda, Allen Ginsberg and Ornette Colman.

Wendy Clarke’s experiences with the new videographic tools at Shirley’s rooftop apartment at the Chelsea Hotel revealed myriad possibilities for this new art form, many of them performative in nature. Early on Wendy discovered video’s potential for the intimacy of self-portraiture as she affirms to MacDonough:

And later in the interview, this pronouncement: “In all the videos I’ve done, seeing [oneself] on the monitor has been an essential part of my work.” Clarke’s description of her first connection to video as an obsessive, first person practice is consistent with the experimentation of many other artists of the period, and here I’m thinking of artists such as Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas and Peter Campus.

And yet, I must stress that the work of Wendy Clarke as it evolved through The Love Tapes by the late 1970s, as well as with later projects in the 1990s such as One on One and L.A. Link, is distinguishable from almost all her video contemporaries making first-person work who, sometimes with great earnestness, sometimes with sly humor, used the camera as a tool for self-discovery and the interrogation of past trauma. A case in point, from a direct to camera monologue from Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Binge (1987): “Right now I’m sitting here with no cameraman in the room. I’m totally alone. I would never, ever talk this way if somebody were in the room, it would insure lying.” Increasingly Clarke altered the terms of her engagement with the medium as a tool for auto-analysis – toward the description she offers in the MacDonough interview: “I envisioned my role as an artist in terms of planning, facilitating, directing, and synthesizing interactive situations. I provided both a base structure and a video format from which the art experience was created through subject-medium interaction.”

For Clarke, after those first diaristic efforts, the subject would become others, but not in the traditional documentary sense of that term. Recall Bill Nichols’s description of the common rhetorical construction of the documentary film: “I speak about them to you,” a play of first, second and third person. This construction is meant to capture the rhetorical and didactic baseline for much nonfiction in which filmmakers leverage engagements with subjects the better to inform and persuade audiences about some facet of social life. It’s a triadic structure that couples the encounter of maker and subject with the address to the audience, hopefully without harm or deception. This is, I would argue, a fraught ethical scenario that involves characterizing others, appropriating their speech or behavior via capture and editing, and adapting it to the filmmaker’s purpose and point of view.

"I make it possible for you to speak about you to you (and maybe then to us)."

Conversely the first-person confessional video might be considered to be a rhetorical instance of “I speak about me to me (and then you),” a play of first and second person. But the Clarke works of which I speak here might be described as “I make it possible for you to speak about you to you (and maybe then to us).” In this instance, Clarke does not exert control over the spoken material or the spatial disposition of subject and background (mise-en-scene); nor does she impose an authorial perspective on it by editing. Instead, she comes to the creative act as the wielder of a conceptual framework (bestowal of the manna-word) and a video apparatus (the monitor and recorder and the looped intimacy it affords), that enables participants to voice their experience, initially for themselves and then, potentially, for a broader, indeed incalculable audience. The audience has included passersby in the public places where the tapes were made, occasional broadcast audiences and now, all those who access the archive.

These are the material conditions of production and exhibition for The Love Tapes. I would argue that these tapes constitute a rather unique creative endeavor, one that enacts something like a deferral of authorial control even while allowing traces of what Derrida has called the “staging” of a signature to remain. The deferral of authorship becomes a defining mark of Clarke’s creative commitment and stance. And it is precisely where ethics makes its entrance.

I can offer here little more than a shorthand version of what I mean by ethics. If the focus of epistemology is knowledge, that of ethics is “the good.” I’m indebted to Emmanuel Levinas, a towering figure in 20th century ethical philosophy who argued that the Other, always unique and irreducible, necessarily commands our attention. “There is a paradox in responsibility,” writes Levinas, “in that I am obliged without this obligation having begun in me, as though an order slipped in my consciousness like a thief… Responsibility for the other… is human fraternity itself, and it is prior to freedom.” The language used to describe ethics in works such as Otherwise than Being, or Beyond Essence – responsibility, obligation, sacrifice, indebtedness – can be contrasted with that associated with knowledge production, construed by Levinas as appropriative, territorializing, even violent. In contrast to the loop of the video confession with which I began, Clarke’s practice, as it evolved through The Love Tapes project, moved away from the assertiveness even aggression of knowledge production to a practice that was inherently relational, bound up in and responsible to what Levinas called “the supreme concreteness of the face of the other man,” rooted in an unlimited engagement with others, hundreds of others.

By the 1980s and into the 1990s, Clarke had moved to California, earned a PhD in psychotherapy, and had taken her art practice into prisons and schools, encouraging others to use video as a tool for self-understanding and to engage in dialogue with others across institutional boundaries. Those exchanges (the One on One and L.A. Link projects mentioned above) were acts of shared intimacy and reciprocity, and were to my mind experiments in ethics and art therapy.

Wendy Clarke now works in close community with the many animals with whom she shares space in her northern New Mexico home: spinning, weaving, drawing, painting, making clothing and artifacts.

Throughout her work, Clarke explored the potential of the video medium for intimacy, self-interrogation, portability, and participatory potential. The next move, the conceptualization and realization of The Love Tapes as a utopic project in which a succession of Others commanded center stage, constitutes Clarke’s greatest contribution to art and culture. It speaks to a rather specific vision of art’s potential and to Clarke’s own personal commitments.

Am I surprised or saddened that Wendy moved away from video decades ago, choosing to make art differently? She works now in close community with the many animals with whom she shares space in her northern New Mexico home: spinning, weaving, drawing, painting, making clothing and artifacts. This path has taken her out of the spotlight. But to become an artist-facilitator is to set aside many of the accoutrements of the artist’s toolkit and identity.

I can’t help but think about the limited analogy to the maker of compilation films for documentary studies. How, I’ve suggested elsewhere, can we ascribe the status of filmmaker to someone who shoots not a foot of film, who records not a single sound? Yet the compilation filmmaker (including the likes of Esfir Schub, Emile de Antonio and Peter Forgacs), retains creative agency, in this instance through the act of editing. In excavating fragments (some might even say the detritus) of the archive, the compilation filmmaker endows old material with new meanings. She revivifies, resurrects and recycles. Like the compilation filmmaker, the artist-facilitator, while anomalous, is still very much the handmaiden to creation. By deferring to Others, she enables the sharing of emotions, experiences and inner worlds previously unknown. In this way, a debt is paid, community is bolstered, small revelations are shared, and utopia is approached if not fully achieved.

Michael Renov is a Professor of Critical Studies and Vice Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of Southern California. He collaborated with Wendy Clarke on many projects while she was in California, including L.A. Link.